+39 0669887260 | info@wucwo.org | Contact us

Art for meditation - June 2021

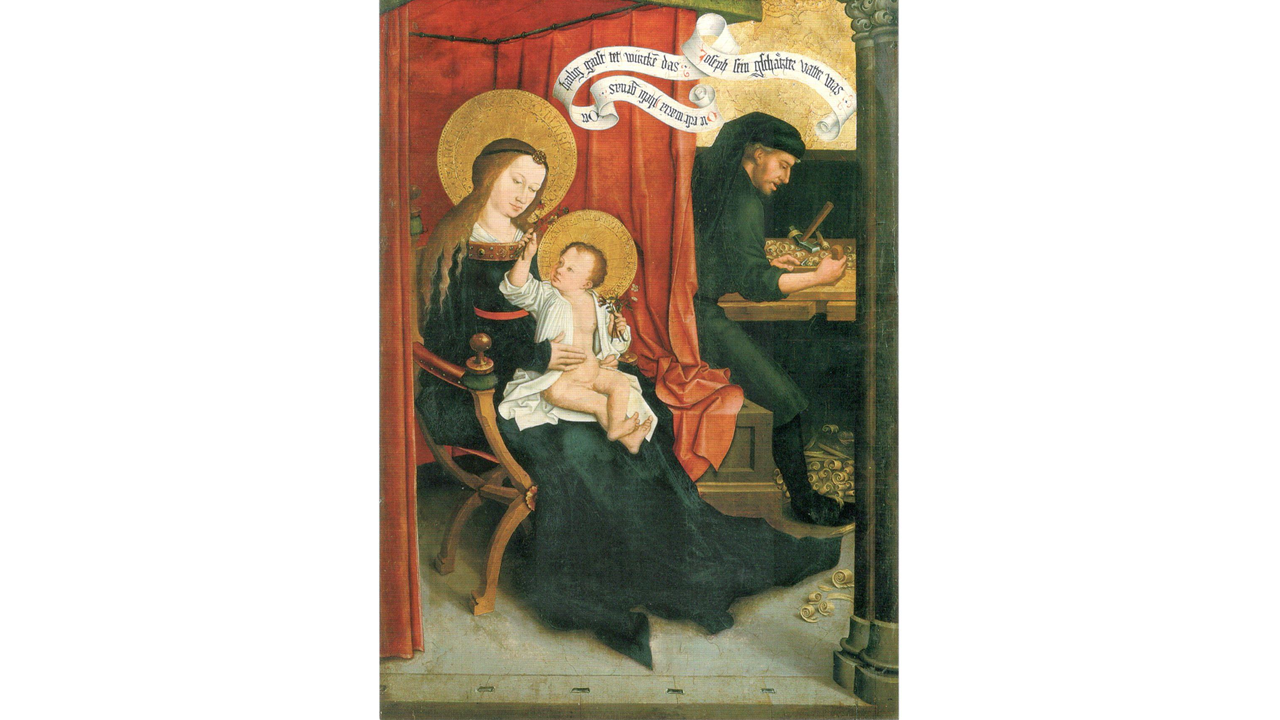

Bernhard Strigel, (Memmingen, Germany 1460 – 1528), Holy Family, 1505-1506, oil on fir wood, 78 cm x 55 cm, Nuremberg, Germany, Germanisches National Museum

Month of June.

The panel, along with nine others, all of them in Nuremberg, was part of the altarpiece of the chapel dedicated to St. Anne in the parish church of Mindelheim, Germany. The chapel was the burial place of the Rechberg and Frundsberg families, who asked the painter to depict the family of Jesus and his ancestors.

Nevertheless, instead of painting a family tree, as was the custom up to that time, the painter placed the family institution at the centre: each panel depicts a family as a whole (mother, father, son or daughter) in a moment of daily life.

The house of Mary and Joseph is very simple, with little furniture and a large red curtain that serves both as a partition and as an element that gives prominence to the figures of the mother and son. Their predominance is also emphasised by both them being on the foreground (whereas Joseph is relegated to the background on the right) and the two large haloes. The chair on which Mary is seated, a so-called Savonarola chair, is no longer a throne, even though the throne on which the infant Jesus is seated is the body of Mary herself, whose dark dress contrasts with the naked body and white blouse of her son.

Let us now focus on Joseph. We cannot fail to notice the realism of the scene. The painter has caught him in his carpenter's trade: the work table, the hand plan with which he is smoothing a board, the hammer, the gimlet. Perhaps what strikes us most are the many curls of wood scattered on the table and on the floor, testifying his hard work. Joseph is absorbed and focused on the work of his hands, because he knows that from his commitment comes the possibility to maintain his beloved family in dignity.

The altarpiece, a votive offering in the church of a small village in Bavaria, was therefore meant as a glorification of the family, the privileged place where the upbringing of children takes place. The members of the Rechberg and Frundsberg families who commissioned the painting from our painter wished to entrust all their loved ones to the Lord and to his intercession, in the certainty that in this way their lives would be in good hands.

I would like to conclude this brief reflection by making my own the invocations that were engraved by the will of the commissioners in the two haloes around the heads of Mary and Jesus:

“Sanctissima Virgo Maria, ora pro nobis” (Mary, Most Holy Virgin, pray for us)

“Iesu Christi fili Dei vivi, miserere nobis” (Jesus, son of the living God, have mercy on us).

“An aspect of Saint Joseph that has been emphasized from the time of the first social Encyclical, Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, is his relation to work. Saint Joseph was a carpenter who earned an honest living to provide for his family. From him, Jesus learned the value, the dignity and the joy of what it means to eat bread that is the fruit of one’s own labour.

In our own day, when employment has once more become a burning social issue, and unemployment at times reaches record levels even in nations that for decades have enjoyed a certain degree of prosperity, there is a renewed need to appreciate the importance of dignified work, of which Saint Joseph is an exemplary patron.”

Pope Francis, apostolic letter Patris Corde 6, 8 December 2020

(Contribution by Vito Pongolini)