+39 0669887260 | info@wucwo.org | Contact us

Art for meditation - April 2020

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), The Deposition, 1507, oil on wood, 184 cm x 176 cm, Rome, Galleria Borghese.

10 April, Good Friday.

This beautiful painting is signed and dated (RAPHAEL URBINAS MDVII) on the rock in the bottom left corner, showing that it was an important work for the painter as well.

The work was commissioned by Atalanta Baglioni to commemorate her son Grifonetto, who was the victim of an episode of unprecedented violence in their city of Perugia, Italy. In fact, on the night of July 3, 1500 Grifonetto, helped by a gang of assassins, decided to get rid of the relatives of his own family, one of the most powerful in the city, in order to gain power. However, Gian Paolo Baglioni escaped from the massacre and that same night he followed in Grifonetto's footsteps, confronted him, challenged him to a duel and eventually killed him.

Atalanta, stunned by the violence caused by her son's behaviour and his murder, asked Raphael, a young genius of painting whose fame was spreading and who had already painted an important painting for the Oddi family in Perugia (see the March article of “Art for Meditation”), an altarpiece to be placed in the altar of the chapel that the Baglioni family had in the church of San Francesco al Prato. The theme, unusual for an altarpiece, was due to the fact that Atalanta wanted her immense pain as a mother to remain forever in the stabbing pain of Mary in front of the dead body of Jesus carried to the tomb.

Raphael worked with great commitment at the opera. Proof of this is the fact that today we still have 16 of his preparatory studies preserved in some of the most famous museums in Europe, whose analysis tells us that the initial idea was to represent a “mourning” on the body of Christ just descended from the cross, and then move to the theme of transport to the tomb.

The main invention was dividing the large square panel into two scenes: on the left is the transport of Christ's now lifeless body - with the evident wounds caused by the nails, with the intense but contained pain on the faces of Joseph of Arimathea, the apostle John, Nicodemus and Magdalene surrounding him; on the right is the scene of the pain of Mary, her mother, which is so great that she fainted and had to be held by the pious women who had accompanied her to the cross.

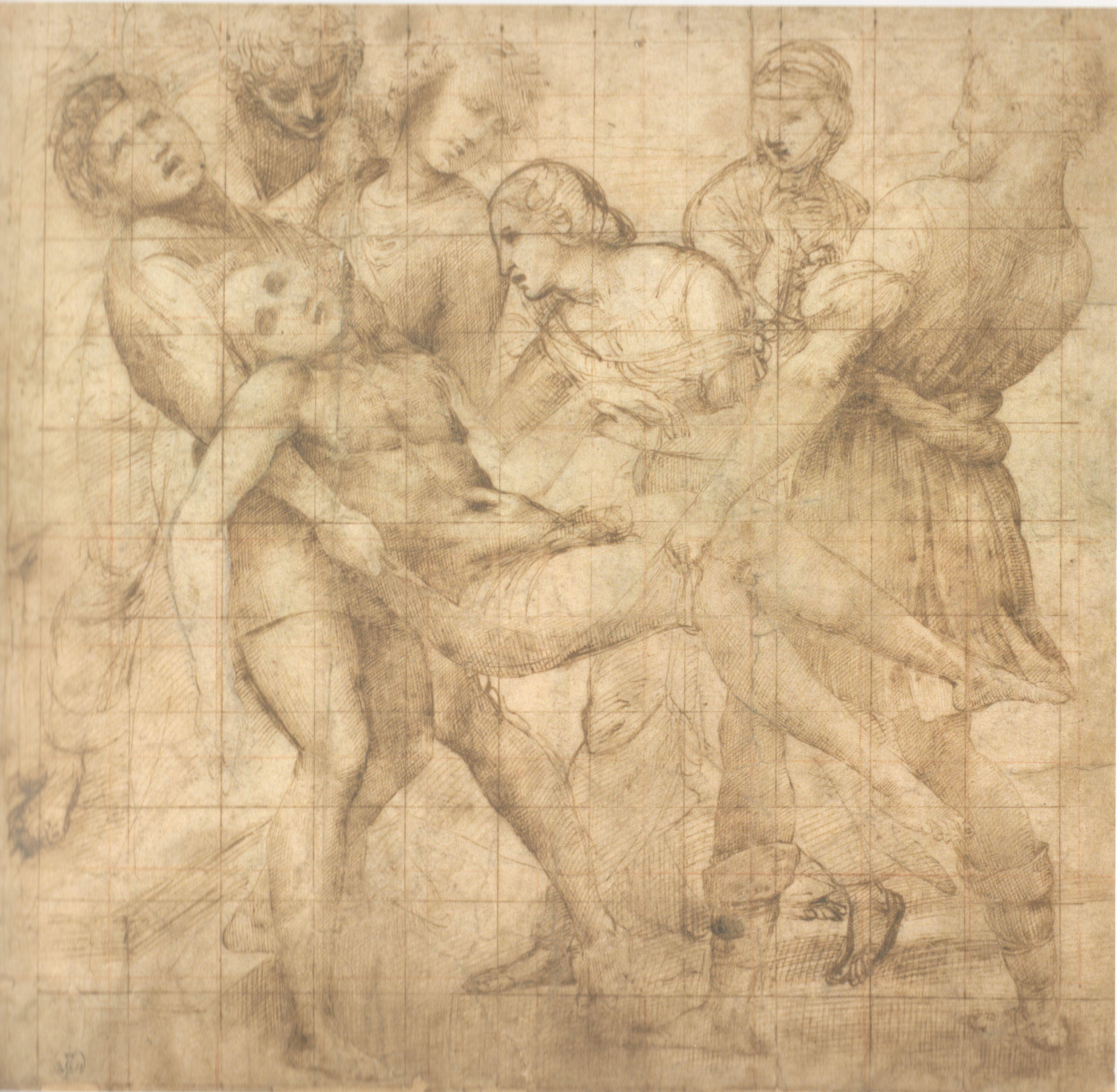

It is interesting now to look at the preparatory study below (it is kept in the Uffizi Museum in Florence, Italy, measures 289 mm x 298 mm, and was made with a brown ink pen and traces of black pencil). Its visible grid means that Raphael considered it to be the last idea to be reproduced proportionally on the large wood. Nevertheless, at the last moment Raphael decided to erase the woman we can see in the study between the Magdalene and the character holding the legs of Christ. This meant that the scene in the painting was no longer a single one, but it had two main focal points instead: the dead body of Christ on the left; the fainted body (seemingly dead) of Mary on the right (note also the correspondence on opposite sides of the painting between the right hand of Christ and the left hand of the Virgin).

The link between these two groups is the magnificent figure of the young man with the red shirt and green robe: he is in fact one of those who are carrying the body of Jesus (left group) but his body is arched backwards for the effort, thus making him one with the right group of the pious women and Mary.

Let's take a last look at this character: indicated by some as a portrait of the deceased Grifonetto, it seems to be a supernatural figure, either because of his sturdiness, or because of his hair, which seems to be moved more by a supernatural force than by the wind, of which there is no trace in the painting.

While contemplating this scene, in particular on Easter days and in this time overshadowed by the pandemic that so much grief and mourning has sown and is sowing in the world, we address our prayers to the Lord in the words of the psalmist:

You who live in the secret place of Elyon, spend your nights in the shelter of Shaddai,

saying to the Lord, 'My refuge, my fortress, my God in whom I trust!'

He rescues you from the snare of the fowler set on destruction;

he covers you with his pinions, you find shelter under his wings.

His constancy is shield and protection.

You need not fear the terrors of night, the arrow that flies in the daytime,

the plague that stalks in the darkness, the scourge that wreaks havoc at high noon.

Though a thousand fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, you yourself will remain unscathed.

You have only to keep your eyes open to see how the wicked are repaid,

you who say, 'The Lord my refuge!' and make Elyon your fortress.

No disaster can overtake you, no plague come near your tent;

he has given his angels orders about you to guard you wherever you go.

They will carry you in their arms in case you trip over a stone.

You will walk upon wild beast and adder, you will trample young lions and snakes.

'Since he clings to me I rescue him, I raise him high, since he acknowledges my name.

He calls to me and I answer him: in distress I am at his side, I rescue him and bring him honour.

I shall satisfy him with long life, and grant him to see my salvation.'

(Psalm 91)

Personal note

Monday, April 6 marks the exact 500th anniversary of Raphael's death in 1520 in Rome, when he was only 37 years old. While I regret a death so premature that it has certainly deprived us of many other masterpieces, I would like to thank the Lord for this life that still today gives us beauty and joy to the heart.

V.P.