+39 0669887260 | info@wucwo.org | Contact us

You are here: Home

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Seville 1618 - 1682), Boys playing dice, around 1675/80, oil on canvas, 146 x 108.5 cm, Munich, Alte Pinakothek

Signs of hope: the poor

There are several paintings that the great Spanish painter dedicated to the childhood which he could probably observe every day on the streets of Seville. They are vivid testimonies of the great poverty in which the majority of the population of Andalusia's most important city lived at the end of the 17th century.

This magnificent painting also presents this reality to us. It does so, first of all, by showing how the three protagonists are dressed: threadbare, dirty clothes, barefoot or wearing shoes with soles so worn that half their feet show through. The very fact that they spend their time on the street playing dice with the few coins we are able to see, tells us of a degraded human environment, where the little ones are left at the mercy of the street, with all the dangers that this entails.

Image is used from www.hermitagemuseum.org, courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen 1577 - Antwerp 1640), Roman Charity (Cimon and Pero), c. 1612, oil on canvas (transferred from panel, 140.5 x 180.3 cm, St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum

Signs of hope: the prisoners.

The story that this beautiful painting by Rubens illustrates is told in the ‘Nine Books of Memorable Sayings and Facts’ by the Latin historian Valerius Maximus. A Roman woman, Pero, secretly breastfeeds her father, Cimon, who has been imprisoned and condemned to death by starvation. She is discovered and denounced by a guard, but her courage and filial piety so impress the prison officials that they grant her father's release.

Hans Memling (Selingenstadt c. 1430 - Bruges 1494), Portrait of an Elderly Woman, 1470-72, oil on panel, 35 x 29 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

Signs of hope: the elderly.

It is not all that often in the world of painting that one comes across a portrait of an elderly person. There are many reasons for this, such as the fact that centuries ago the average age was much lower and there were far fewer elderly people than today, or because it was believed that beauty fades with age and therefore, for an art that tended towards perfection, the elderly person was not an interesting subject.

The beautiful portrait painted by the great Flemish painter Hans Memling in the second half of the 15th century is certainly an interesting example that tells us several things about old age and the consideration it might have received at that time.

Louise-Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun (Paris 1755 - 1842), Madame Vigée-Le Brun and her daughter, Jeanne-Lucie-Louise, known as Julie, 1789, oil on panel, 130 x 94 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

The signs of hope: generating new sons and daughters

In the first months of this new year, we allow ourselves to be accompanied by the Jubilee spirit that the whole Church intends to live. We are doing so with a particular slant: we intend to propose for reflection and contemplation some figures of women who embody, in the representations made by artists from different eras and places, what Pope Francis called - in the bull of Jubilee proclamation - ‘signs of hope’.

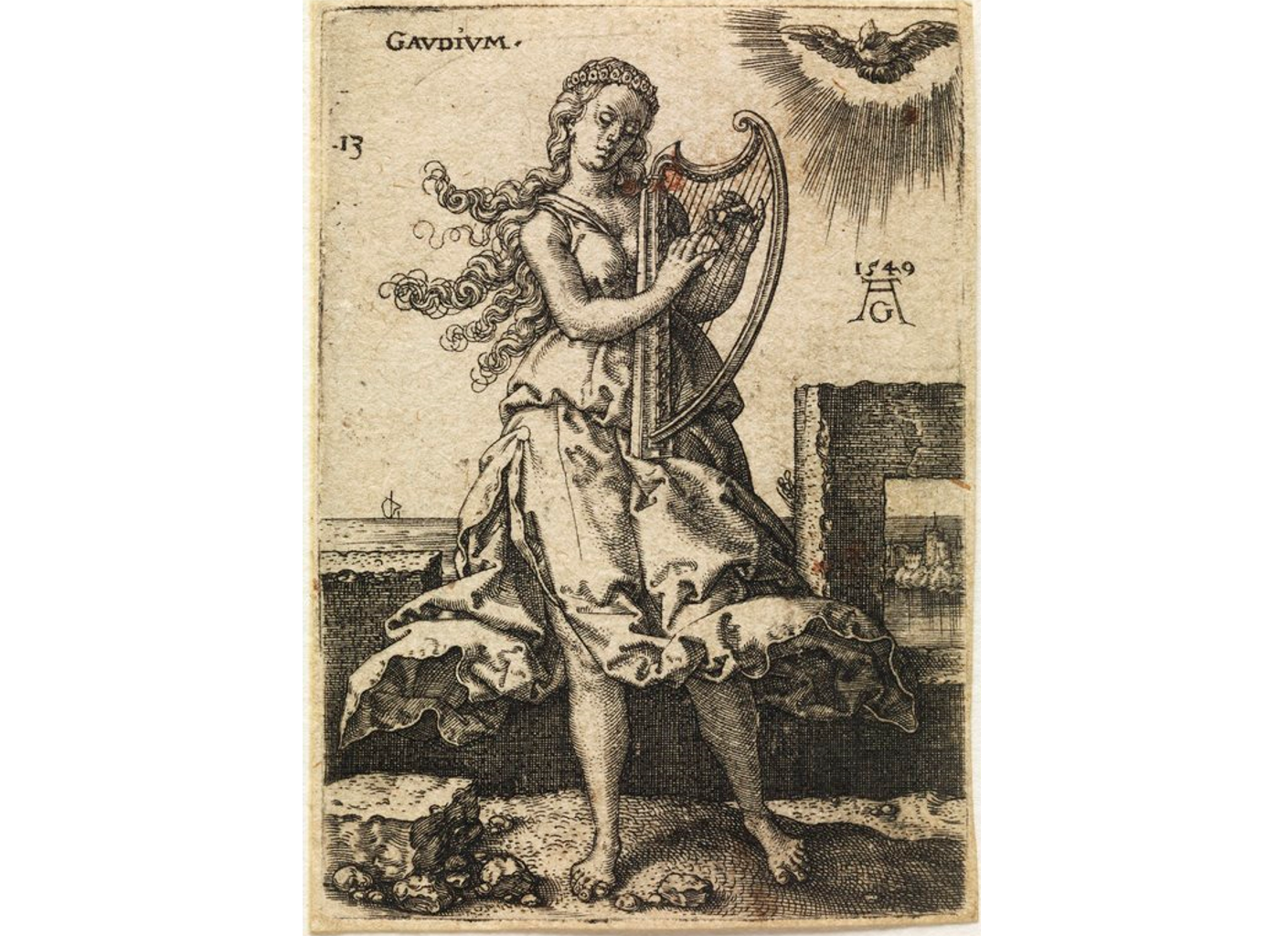

Heinrich Aldegrever (Paderborn 1502 - Soest ca. 1560), The Joy, 1549, engraving on paper, 7.2 x 5.2 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

Heinrich Aldegrever (Paderborn 1502 - Soest ca. 1560), The Joy, 1549, engraving on paper, 7.2 x 5.2 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Virtues: Joy

We end our presentation of the virtues with which we have accompanied this year 2024 with an engraving by a refined German artist. In 1549 he engraved 14 small plates each representing a vice or a virtue.

We do not know who commissioned this work and for what purpose, but we are struck by the choice to entrust the description of each subject to a simple and apparently poor medium. The engraving, in fact, unlike the painting that in the use of colour finds a powerful ally for the rendering of figures and moods, plays everything on line and luminosity that is due to the lesser or greater incidence of solids and voids. Aldegrever was completely satisfied with the outcome of his work, so much so that in each of the 14 engravings we find both the year of composition and the initials of his name.

Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen 1577 - Antwerp 1640), The Triumph of Truth, 1622-25, oil on canvas, 394 x 160 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Virtues: Truth.

The painting is the last of 24 that Rubens painted to decorate the western gallery on the first floor of the Luxembourg Palace, built in those same years by Maria de' Medici, Queen of France and wife of King Henry IV, who wanted to make it her residence.

Eugène Delacroix (Charenton-Saint-Maurice 1798 - Paris 1863), Liberty Leading the People, 1830, oil on canvas, 360 x 325 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Virtues: Liberty.

Eugène Delacroix's famous painting takes its cue from an event that really took place: in July 1830, from the 27th to the 29th, the people of Paris rebelled against the government that King Charles X had set up the year before. They made barricades and forced the king to dismiss the government, cancel the liberticidal laws that had been enacted and finally abdicate by fleeing to England.

Luca Giordano (Naples 1634 - 1705), Allegory of the divine Wisdom, 1680 circa, oil on canvas, cm 138,5 x 65,2, London, National Gallery

The virtues: the divine Wisdom

Luca Giordano was called by the marquis Francesco Riccardi to fresco some rooms built to expand the Florentine palace that the rich family had bought in 1659 from the Medici, their allies. This model, or detailed oil study, is part of a group of 12 that Giordano made in preparation for the ceiling frescoes of Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence in 1682-85. The general theme of these highly elaborate and impressive frescoes is the progress of humanity through wisdom and virtue.

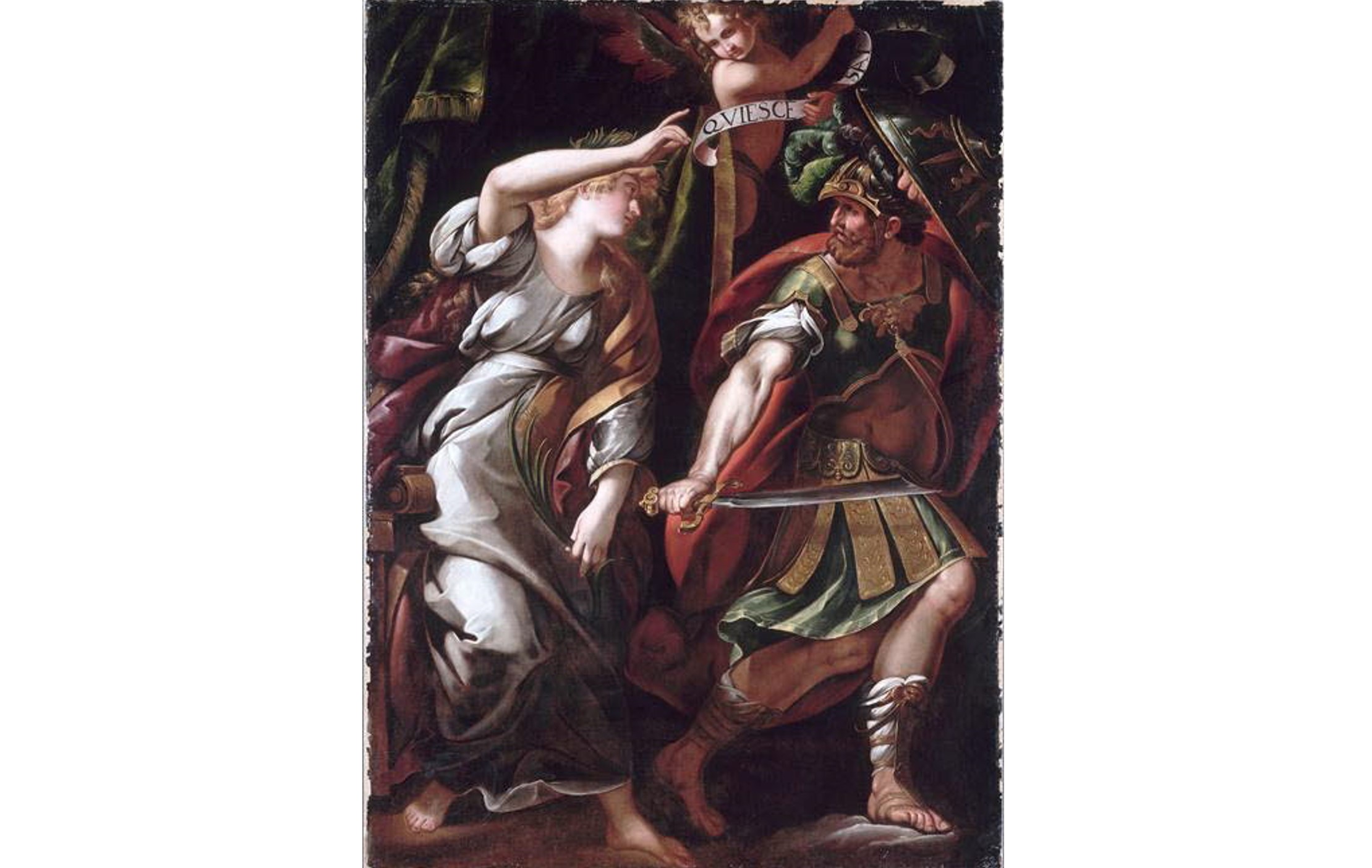

Giulio Cesare Procaccini (Bologna 1574 - Milan 1625), Peace chasing War, c. 1610, oil on canvas, 235 x 171 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Virtues: Peace

The beauty and power of this painting lies in the contrast between the two protagonists on the canvas, Peace and War, personified respectively by a young woman and a mature man with a beard.

The delicate and gentle figure of Peace occupies the left side of the painting, while War occupies the right side. But we notice a movement of the two figures, from left to right, which tells us that soon Peace will be the only protagonist, because War is about to leave the scene.

Piero del Pollaiolo (Florence 1441 - Rome 1496), La Temperanza, 1470, tempera grassa on panel, 168 x 90.5 cm, Florence, Uffizi Museum

The virtues: the Temperance

We would also like to begin this reflection with the words of Pope Francis, who dedicated the audience on Wednesday 17 April to the last of the "cardinal" virtues, the Temperance. And he reminded us that it “is the virtue of the right measure. In every situation, one behaves wisely, because people who act always moved by impulse or exuberance are ultimately unreliable. People without temperance are always unreliable. In a world where many people boast about saying what they think, the temperate person instead prefers to think about what he says. Do you understand the difference? Not saying whatever comes into my mind, like so… no: thinking about what I have to say. He does not make empty promises but makes commitments to the extent that he can fulfil them.”

Piero del Pollaiolo (Florence 1441 - Rome 1496), Prudence, 1469-72, tempera grassa on panel, 168 x 90.5 cm, Florence, Uffizi Museum

The Virtues: Prudence

Pope Francis dedicated his Wednesday 20 March audience to the first of the "cardinal" virtues, prudence. And he reminded us that “Prudence is the capacity to govern actions in order to direct them towards good; for this reason, it is dubbed the “coachman of the virtues”. Prudent are those who are able to choose. As long as it remains on paper, life is always easy, but in the midst of the wind and waves of daily life it is another matter; often we are uncertain and do not know which way to go. The prudent do not choose at random: first of all, they know what they want, then they weigh the situation, seek advice, and with a broad outlook and inner freedom, they choose upon which path to embark”.

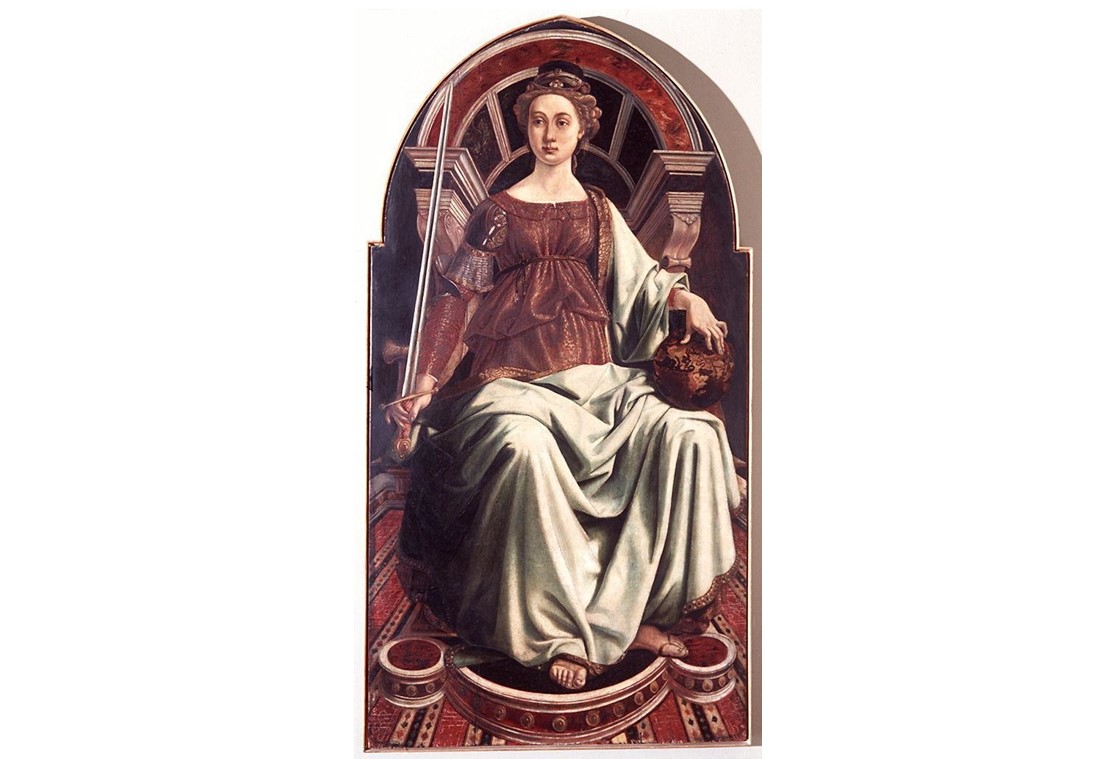

Piero del Pollaiolo (Florence 1441 - Rome 1496), Justice, 1469-72, tempera grassa on panel, 168 x 90.5 cm, Florence, Museo degli Uffizi

The Virtues: Justice.

Last April, Pope Francis - who has dedicated all of this year's general audiences to the vices and virtues - spoke about the second of the 'cardinal' virtues, Justice, in his Wednesday 3 April audience.

He began his catechesis by saying that justice ‘is the social virtue par excellence. The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines it thus: “The moral virtue that consists in the constant and firm will to give their due to God and neighbor” (no. 1807). This is justice. Often, when justice is mentioned, the motto that represents it is also quoted: 'unicuique suum', that is, “may all get their due”. It is the virtue of law, which seeks to regulate relations between people with equity'.

Sandro Botticelli (Florence 1445 - 1510), The Fortitude, 1470, tempera grassa on panel, 167 x 87 cm, Florence, Uffizi Museum

The Virtues: The Fortitude.

With the month of April, our journey of discovery of the virtues takes a step forward and we enter the first of the so-called 'cardinal' virtues, namely the Fortitude. If we open the Catechism of the Catholic Church, it tells us that " Human virtues are firm attitudes, stable dispositions, habitual perfections of intellect and will that govern our actions, order our passions, and guide our conduct according to reason and faith. They make possible ease, self-mastery, and joy in leading a morally good life. the virtuous man is he who freely practices the good. The moral virtues are acquired by human effort. They are the fruit and seed of morally good acts; they dispose all the powers of the human being for communion with divine love. " (No. 1804).

Piero del Pollaiolo (Florence 1441 - Rome 1496), Charity, 1469-70, tempera grassa on panel, 168 x 90.5 cm, Florence, Uffizi Museum

The Virtues: Charity

This month, leading up to Easter, we examine the third of the theological virtues, Charity. Art historians tell us that this was in fact the first panel of the cycle of virtues painted by Piero del Pollaiolo and that it was presented to the heads of the Tribunale della Mercanzia in order to obtain the work: the proclamation in fact foresaw the execution of seven panels to represent all the virtues, both the "theological" and the "cardinal" ones. The work was liked and so the painter was contracted to execute the other works as well.

Piero del Pollaiolo (Florence 1441 - Rome 1496), La Speranza, 1469-72, tempera grassa on panel, 168 x 90.5 cm, Florence, Uffizi Museum

The virtues: Hope

We continue to examine the pictorial cycle dedicated to the Virtues that was commissioned to Piero del Pollaiolo in 1469 and destined for the Audience Room in the Tribunale di Mercanzia in Piazza della Signoria in Florence.

Before examining the second painting in the cycle, let us recall what we mean when we speak of the "theological" virtues (faith, which we wrote about last month, hope and then charity). In the Catechism of the Catholic Church we read: “the theological virtues relate directly to God. They dispose Christians to live in a relationship with the Holy Trinity. They have the One and Triune God for their origin, motive, and object. The theological virtues are the foundation of Christian moral activity; they animate it and give it its special character. They inform and give life to all the moral virtues. They are infused by God into the souls of the faithful to make them capable of acting as his children and of meriting eternal life. They are the pledge of the presence and action of the Holy Spirit in the faculties of the human being. There are three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity”. (Nº 1812-1813).

Piero del Pollaiolo (Florence 1441 - Rome 1496), The Faith, 1470, tempera grassa on panel, 168 x 90.5 cm, Florence, Uffizi Museum

The Virtues: Faith

In this New Year, we would like to offer for reflection and contemplation figures of women that we can certainly define as "special": these are the personifications that artists of the past have made in an attempt to represent the virtues. They are always depicted as women as if to emphasise the indissoluble link between the 'habitual and firm disposition to do the good' (definition of virtue found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church 1803) and the female gender.

This first work, depicting Faith, is part of a cycle of paintings dedicated to the Virtues, commissioned to Piero del Pollaiolo in 1469 and destined for the Sala dell'Udienza of the Tribunale di Mercanzia (the body that heard the commercial disputes of Florentine merchants and administered justice among the members of the arts & crafts) in Piazza della Signoria in Florence.

© 2014 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec

Veronese, Paolo Caliari called (Verona 1528 - Venice 1588), The Resurrection of the Daughter of Jairus, c. 1546, oil on paper pasted on canvas, 42 x 37 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre

Women of the New Testament: The Daughter of Jairus.

When Jesus returned, the crowd welcomed him, for they were all waiting for him. And a man named Jairus, an official of the synagogue, came forward. He fell at the feet of Jesus and begged him to come to his house, because he had an only daughter, about twelve years old, and she was dying. As he went, the crowds almost crushed him. And a woman afflicted with hemorrhages for twelve years, who (had spent her whole livelihood on doctors and) was unable to be cured by anyone, came up behind him and touched the tassel on his cloak. Immediately her bleeding stopped.

Veronese, Paolo Caliari said the (Verona 1528 - Venice 1588), Christ and the Samaritan, about 1585, oil on canvas, 143.5 x 288.3 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Veronese, Paolo Caliari said the (Verona 1528 - Venice 1588), Christ and the Samaritan, about 1585, oil on canvas, 143.5 x 288.3 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Month of November.

Women of the New Testament: the Samaritan.

He had to pass through Samaria. So he came to a town of Samaria called Sychar, near the plot of land that Jacob had given to his son Joseph. Jacob's well was there. Jesus, tired from his journey, sat down there at the well. It was about noon. A woman of Samaria came to draw water. Jesus said to her, "Give me a drink." His disciples had gone into the town to buy food. The Samaritan woman said to him, "How can you, a Jew, ask me, a Samaritan woman, for a drink?" (For Jews use nothing in common with Samaritans.)

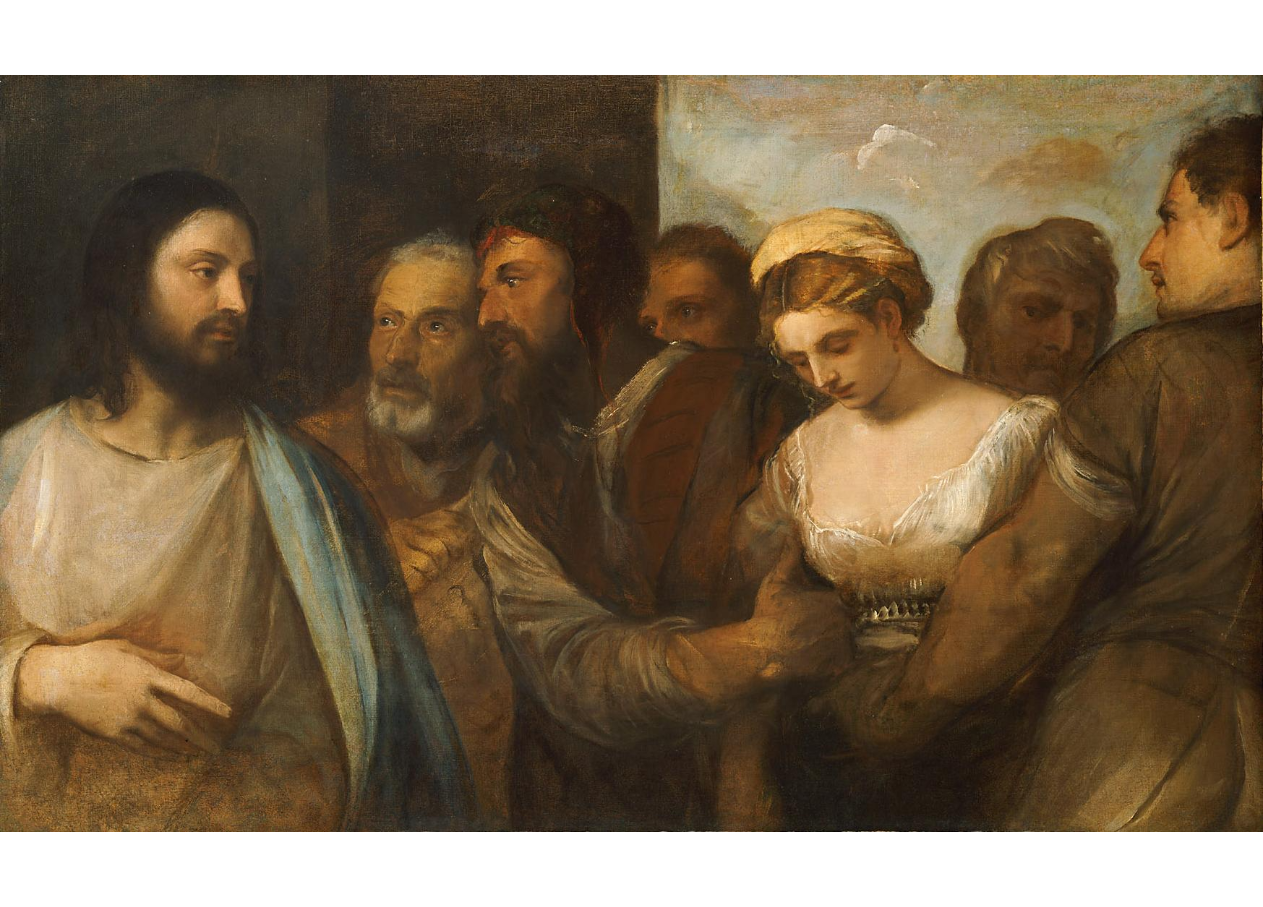

Tiziano Vecelio (Pieve di Cadore c. 1488 - Venice 1576), Christ and the Adulteress, c. 1512/15, oil on canvas, 82.5 x 136.5 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Month of October.

Women of the New Testament: The Adulteress.

While Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. But early in the morning he arrived again in the temple area, and all the people started coming to him, and he sat down and taught them. Then the scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery and made her stand in the middle. They said to him, "Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. Now in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. 2 So what do you say?" They said this to test him, so that they could have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and began to write on the ground with his finger. But when they continued asking him, he straightened up and said to them, "Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her." Again he bent down and wrote on the ground. And in response, they went away one by one, beginning with the elders. So he was left alone with the woman before him. Then Jesus straightened up and said to her, "Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?" She replied, "No one, sir." Then Jesus said, "Neither do I condemn you. Go, (and) from now on do not sin any more." (John 8, 1-11)

Master of Saint Veronica (active between 1400 and 1425), St. Veronica with the Holy Kerchief, c. 1425, oil on panel (fir wood), 78.1 x 48.2 cm, Munich, Alte Pinakothek

Women of the New Testament: Veronica.

Accompanying him were the Twelve and some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities, Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, Joanna, the wife of Herod's steward Chuza, Susanna, and many others who provided for them out of their resources. (Lk 8:2-3)

The women who had come from Galilee with him followed behind, and when they had seen the tomb and the way in which his body was laid in it, they returned and prepared spices and perfumed oils. Then they rested on the sabbath according to the commandment. (Lk 23:55-56)

Dierick Bouts (Haarlem c.1410– Louvain 1475), Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee, between 1450 and 1475, oil on wood, cm 42.2 x 62.5 cm, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

Month of August.

New Testament women: the Sinner in the House of Simon.

A Pharisee invited him to dine with him, and he entered the Pharisee's house and reclined at table. Now there was a sinful woman in the city who learned that he was at table in the house of the Pharisee. Bringing an alabaster flask of ointment, she stood behind him at his feet weeping and began to bathe his feet with her tears. Then she wiped them with her hair, kissed them, and anointed them with the ointment.

José de Ribera (Játiva, Valencia 1591 – Napoli 1652), Penitent Magdalene, 1641, oil on canvas, cm 182 x 149, Madrid, Prado Museum.

José de Ribera (Játiva, Valencia 1591 – Napoli 1652), Penitent Magdalene, 1641, oil on canvas, cm 182 x 149, Madrid, Prado Museum.

Month of July.

New Testament women: Mary Magdalene.

Afterward, he journeyed from one town and village to another, preaching and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God. Accompanying him were the Twelve and some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities, Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, Joanna, the wife of Herod's steward Chuza, Susanna, and many others who provided for them out of their resources. (Lk 8, 1-3)

Veronese - Paolo Caliari (Verona 1528 - Venice 1588), La risurrezione del giovane di Nain, 1565-70, oil on canvas, cm 102 x 136, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Veronese - Paolo Caliari (Verona 1528 - Venice 1588), La risurrezione del giovane di Nain, 1565-70, oil on canvas, cm 102 x 136, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Month of June.

New Testament women: Nain’s widow.

Soon afterward he journeyed to a city called Nain, and his disciples and a large crowd accompanied him. As he drew near to the gate of the city, a man who had died was being carried out, the only son of his mother, and she was a widow. A large crowd from the city was with her. When the Lord saw her, he was moved with pity for her and said to her, “Do not weep.” He stepped forward and touched the coffin; at this the bearers halted, and he said, “Young man, I tell you, arise!” The dead man sat up and began to speak, and Jesus gave him to his mother. Fear seized them all, and they glorified God, exclaiming, “A great prophet has arisen in our midst,” and “God has visited his people.” This report about him spread through the whole of Judea and in all the surrounding region.(Lc 7, 11-17)

Diego Velázquez (Seville 1599 - Madrid 1660), Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618, oil on canvas, 60 x 103.5 cm, London, National Gallery.

Diego Velázquez (Seville 1599 - Madrid 1660), Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618, oil on canvas, 60 x 103.5 cm, London, National Gallery.

Month of May.

New Testament women: Martha, Mary’s sister.

As they continued their journey he entered a village where a woman whose name was Martha welcomed him. She had a sister named Mary (who) sat beside the Lord at his feet listening to him speak. Martha, burdened with much serving, came to him and said, "Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me by myself to do the serving? Tell her to help me." The Lord said to her in reply, "Martha, Martha, you are anxious and worried about many things. There is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part and it will not be taken from her." (Lc 10, 38-42)

The image is taken from: www.hermitagemuseum.org, by kind permission of the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The image is taken from: www.hermitagemuseum.org, by kind permission of the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Maurice Denis (Granville 1870 – Saint-Germaine-en-Laye 1943), Martha and Mary, 1896, oil on canvas, 77 x 116 cm, Saint Petersburg, Hermitage Museum.

Month of April.

Women of the New Testament: Mary, sister of Martha and Lazarus.

As they continued their journey he entered a village where a woman whose name was Martha welcomed him. She had a sister named Mary (who) sat beside the Lord at his feet listening to him speak. Martha, burdened with much serving, came to him and said, "Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me by myself to do the serving? Tell her to help me." The Lord said to her in reply, "Martha, Martha, you are anxious and worried about many things. There is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part and it will not be taken from her. (Lk 10, 38-42)

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijin (Leida 1606 – Amsterdam 1669), Anne the Prophetess, 1639, oil on oak wood, oval of 79,5 x 61,7 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijin (Leida 1606 – Amsterdam 1669), Anne the Prophetess, 1639, oil on oak wood, oval of 79,5 x 61,7 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Month of March.

Women of the New Testament: Anne.

There was a prophetess, too, Anna the daughter of Phanuel, of the tribe of Asher. She was advanced in year, having lived seven years with her husband after her marriage, and then as a widow until she was eighty-four. She never left the temple, but worshiped night and day with fasting and prayer. And coming forward at that very time, she gave thanks to God and spoke about the child to all who were awaiting the redemption of Jerusalem. (Lk 2, 36-38)

Giulio Romano (Rome 1499 - Mantova 1546) and Giovanni Francesco Penni (Florence 1496 - Mantova 1528), The Visitation, c. 1517, oil on canvas, 200 x 145 cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado.

Month of February.

Women of the New Testament: Elizabeth.

During those days Mary set out and travelled to the hill country in haste to a town of Judah, where she entered the house of Zechariah and greeted Elizabeth. When Elizabeth heard Mary's greeting, the infant leaped in her womb, and Elizabeth, filled with the holy Spirit, cried out in a loud voice and said, "Most blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb. And how does this happen to me, that the mother of my Lord 14 should come to me? For at the moment the sound of your greeting reached my ears, the infant in my womb leaped for joy. Blessed are you who believed 15 that what was spoken to you by the Lord would be fulfilled”. (Lk 1, 39-45)

Hans Memling (Selingenstadt 1433 approx. - Bruges 1494), Madonna and Child, 1487, oil of oak, 54.6 x 43.2 cm, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie.

Month of January.

Women of the New Testament: Mary.

In the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth, to a virgin engaged to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David. The virgin's name was Mary. And he came to her and said, "Greetings, favoured one! The Lord is with you." But she was much perplexed by his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be. The angel said to her, "Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favour with God. And now, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus. He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his ancestor David. He will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end."

Albrecht Dürer (Norimberga 1471 – 1528), Eva, 1507, oil on board, cm 209 x 80 cm, Madrid, Prado Museum.

Albrecht Dürer (Norimberga 1471 – 1528), Eva, 1507, oil on board, cm 209 x 80 cm, Madrid, Prado Museum.

Month of December.

Women of the Old Testament: Eve.

Then God said: "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. Let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and the cattle, and over all the wild animals and all the creatures that crawl on the ground." God created man in his image; in the divine image he created him; male and female he created them. God blessed them, saying: "Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it. Have dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and all the living things that move on the earth." God also said: "See, I give you every seed-bearing plant all over the earth and every tree that has seed-bearing fruit on it to be your food; and to all the animals of the land, all the birds of the air, and all the living creatures that crawl on the ground, I give all the green plants for food." And so it happened. God looked at everything he had made, and he found it very good. Evening came, and morning followed - the sixth day.

Denys Calvaert (Antwerp 1540 ca. – Bologna 1619), Abraham and the Three Angels, ca. 1600, oil on canvas, 147 x 161 cm, Madrid, Prado Museum.

Month of November.

Women of the Old Testament: Sarah.

The Lord appeared to Abraham by the terebinth of Mamre, as he sat in the entrance of his tent, while the day was growing hot. Looking up, he saw three men standing nearby. When he saw them, he ran from the entrance of the tent to greet them; and bowing to the ground, he said: "Sir, if I may ask you this favor, please do not go on past your servant. Let some water be brought, that you may bathe your feet, and then rest yourselves under the tree. Now that you have come this close to your servant, let me bring you a little food, that you may refresh yourselves; and afterward you may go on your way." "Very well," they replied, "do as you have said." Abraham hastened into the tent and told Sarah, "Quick, three seahs of fine flour! Knead it and make rolls." He ran to the herd, picked out a tender, choice steer, and gave it to a servant, who quickly prepared it. Then he got some curds and milk, as well as the steer that had been prepared, and set these before them; and he waited on them under the tree while they ate. "Where is your wife Sarah?" they asked him. "There in the tent," he replied. One of them said, "I will surely return to you about this time next year, and Sarah will then have a son." Sarah was listening at the entrance of the tent, just behind him. Now Abraham and Sarah were old, advanced in years, and Sarah had stopped having her womanly periods.So Sarah laughed to herself and said, "Now that I am so withered and my husband is so old, am I still to have sexual pleasure?" But the LORD said to Abraham: "Why did Sarah laugh and say, 'Shall I really bear a child, old as I am?’ Is anything too marvelous for the LORD to do? At the appointed time, about this time next year, I will return to you, and Sarah will have a son." Because she was afraid, Sarah dissembled, saying, "I didn't laugh." But he said, "Yes you did." (Gen 18:1-15)

Palma il Vecchio, Jacopo Nigretti de Lavalle (Serina ca. 1480 - Venice 1528), Jacob and Rachel, ca. 1524/25, oil on canvas, 146,5 x 250,5 cm, Dresde, Gemäldegalerie.

Palma il Vecchio, Jacopo Nigretti de Lavalle (Serina ca. 1480 - Venice 1528), Jacob and Rachel, ca. 1524/25, oil on canvas, 146,5 x 250,5 cm, Dresde, Gemäldegalerie.

Month of October.

Women of the Old Testament: Rachel.

Then Jacob continued on his journey and came to the land of the eastern peoples. There he saw a well in the open country, with three flocks of sheep lying near it because the flocks were watered from that well. The stone over the mouth of the well was large. When all the flocks were gathered there, the shepherds would roll the stone away from the well’s mouth and water the sheep. Then they would return the stone to its place over the mouth of the well. Jacob asked the shepherds, “My brothers, where are you from?” “We’re from Harran,” they replied. He said to them, “Do you know Laban, Nahor’s grandson?” “Yes, we know him,” they answered. Then Jacob asked them, “Is he well?” “Yes, he is,” they said, “and here comes his daughter Rachel with the sheep”.“Look,” he said, “the sun is still high; it is not time for the flocks to be gathered. Water the sheep and take them back to pasture.” “We can’t,” they replied, “until all the flocks are gathered and the stone has been rolled away from the mouth of the well. Then we will water the sheep.”

Konrad Witz (Rottweil c. 1400 - Basel c. 1445), The Queen of Sheba before Solomon, c. 1435, oil on oak, 85.8 x 80.3 cm, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie.

Month of September.

Women of the Old Testament: The Queen of Sheba.

The Queen of Sheba, hearing of Solomon's fame, came to test him with subtle questions. She arrived in Jerusalem with a very numerous retinue, and with camels bearing spices, a large amount of gold, and precious stones. She came to Solomon and questioned him on every subject in which she was interested. King Solomon explained everything she asked about, and there remained nothing hidden from him that he could not explain to her.

Jan van Scorel (Schoorl 1495 - Utrecht 1562), Ruth and Naomi in the Field of Boaz, 1530/40, oil on canvas, 70.5 cm x 57.5 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Jan van Scorel (Schoorl 1495 - Utrecht 1562), Ruth and Naomi in the Field of Boaz, 1530/40, oil on canvas, 70.5 cm x 57.5 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Month of August.

Women of the Old Testament: Ruth and Naomi.

Ruth’s story is told in just four chapters. A small book, bearing her name, for a big story; a small book featuring two women: Ruth and Naomi, her mother-in-law. The two women’s destinies intersect in Moab, where Naomi has emigrated with her husband from Bethlehem to escape the famine. There the two sons get married, and one of the two brides is Ruth. After the death of her husband and children, Naomi (who changes her name: no longer Naomi = joy, gladness, but Mara = bitter, unhappy) returns to Israel and leaves her two daughters-in-law free.

Luca Giordano (Naples, Italy 1634 – 1705), The Prudent Abigail, 1696-97, oil on canvas, 216 cm x 362 cm, Madrid, Prado Museum

Month of July.

Women in the Old Testament: Abigail

Abigail hastily took two hundred loaves, two skins of wine, five sheep ready prepared, five measures of roasted grain, a hundred bunches of raisins and two hundred cakes of figs and loaded them on donkeys. She said to her servants, ‘Go on ahead, I shall follow you’ -- but she did not tell her husband Nabal. As she was riding her donkey down behind a fold in the mountain, David and his men happened to be coming down in her direction; and she met them. […]

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Seville, Spain 1618 – 1682), Rebecca and Eliezer, ca. 1660, oil on canvas, 108 cm x 151.5 cm, Madrid, Prado Museum

Month of June.

Women in the Old Testament: Rebecca.

The servant took ten of his master’s camels and, carrying all kinds of gifts from his master, set out for the city of Nahor in Aram Naharaim. In the evening, at the time when women come out to draw water, he made the camels kneel outside the town near the well. And he said, 'Lord, God of my master Abraham, give me success today and show faithful love to my master Abraham. While I stand by the spring as the young women from the town come out to draw water, I shall say to one of the girls, ‘Please lower your pitcher and let me drink.’ And if she answers, ‘Drink, and I shall water your camels too,’ let her be the one you have decreed for your servant Isaac; by this I shall know you have shown faithful love to my master’. He had not finished speaking when out came Rebecca -- who was the daughter of Bethuel son of Milcah, the wife of Abraham’s brother Nahor -- with a pitcher on her shoulder. The girl was very beautiful, and a virgin; no man had touched her. She went down to the spring, filled her pitcher and came up again. Running towards her, the servant said, ‘Please give me a sip of water from your pitcher.’ She replied, ‘Drink, my lord,’ and quickly lowered her pitcher on her arm and gave him a drink. When she had finished letting him drink, she said, ‘I shall draw water for your camels, too, until they have had enough’ (Genesis 24:10-19).

Jacopo del Sellaio (Florence, Italy 1442 – 1493), The Triumph of Mordecai, around 1485, tempera on wood, 44.5 cm x 60 cm, Florence, Italy, Uffizi Gallery.

Month of May.

Women in the Old Testament: Esther.

The story of Esther is told in the book of the same name in the Bible. It consists of 10 short chapters which tell of Aman, a powerful prince at the court of King Ahasuerus (better known by the name of Xerxes), and his evil intention to destroy all the Jews living on Persian territory, in order to take revenge on Mordecai, a Jew who had refused to bow down at his feet.

©Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano

Giovan Francesco Barbieri, known as Guercino (Cento, Italy 1591 – Bologna, Italy 1666), Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael, 1657, oil on canvas, 115 cm x 152 cm, Milano, Italy, Pinacoteca di Brera.

Month of April.

Women in the Old Testament: Hagar.

The origin of this painting is well known. It was commissioned by the community of Cento, who wanted to pay homage to the cardinal legate of Ferrara, Lorenzo Imperiali. We do not know the reason for the choice of subject, but we do know that what the painting shows us is narrated in chapter 21 of the Book of Genesis. Already in chapter 16 it is recounted that Sarah, Abraham’s wife, unable to have children, suggested to her husband that he give a son to his slave Hagar so that her husband could have an offspring. This is fulfilled and, although there is some tension between the two women, it is smoothed over by the intervention of the angel of the Lord. “Hagar bore Abraham a son, and Abraham gave his son borne by Hagar the name Ishmael. Abraham was eighty-six years old when Hagar bore him Ishmael” (Gen 16:15-16).

Sandro Botticelli (Florence, Italy 1445 – 1510), The Return of Judith to Bethulia, 1572, tempera on board, 31 cm x 25 cm, Florence, Uffizi Gallery

Month of March.

Women in the Old Testament: Judith.

The whole story of Judith is told in the short book of the Bible that bears her name. In 16 chapters, the story narrates the descent of the Assyrian army on Israel, the pride and arrogance shown by Holofernes, Nebuchadnezzar’s supreme commander, and his decision to lay siege to the city of Bethulia, occupying in particular the Israelites’ aqueducts and water sources.

© KHM-Museumsverband

Jacopo Robusti, known as Tintoretto (Venice 1518 – 1594), Susanna Bathing, around 1555-56, oil on canvas, 187 cm x 220 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Month of February.

Women in the Old Testament: Susanna.

In Babylon there lived a man named Joakim. He had married Susanna, daughter of Hilkiah, a woman of great beauty; and she was God-fearing, because her parents were worthy people and had instructed their daughter in the Law of Moses. Joakim was a very rich man, and had a garden attached to his house; the Jews would often visit him since he was held in greater respect than any other man. Two elderly men had been selected from the people that year to act as judges. Of such the Lord said, ‘Wickedness has come to Babylon through the elders and judges posing as guides to the people’. These men were often at Joakim’s house, and all who were engaged in litigation used to come to them. At midday, when everyone had gone, Susanna used to take a walk in her husband’s garden. (Daniel 13:1-7)

©Museo Nacional del Prado ©Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional del Prado

Paolo Caliari, known as Paolo Veronese (Verona, Italy 1528 – Venice, Italy 1588), The Finding of Moses, around 1580, oil on canvas, 57 cm x 43 cm, Madrid, Spain, Prado Museum

Month of January.

Women in the Old Testament: Pharaoh’s daughter

There was a man descended from Levi who had taken a woman of Levi as his wife. She conceived and gave birth to a son and, seeing what a fine child he was, she kept him hidden for three months. When she could hide him no longer, she got a papyrus basket for him; coating it with bitumen and pitch, she put the child inside and laid it among the reeds at the River's edge. His sister took up position some distance away to see what would happen to him. Now Pharaoh's daughter went down to bathe in the river, while her maids walked along the riverside. Among the reeds she noticed the basket, and she sent her maid to fetch it. She opened it and saw the child: the baby was crying. Feeling sorry for it, she said, 'This is one of the little Hebrews.' The child's sister then said to Pharaoh's daughter, 'Shall I go and find you a nurse among the Hebrew women to nurse the child for you?' 'Yes,' said Pharaoh's daughter, and the girl went and called the child's own mother. Pharaoh's daughter said to her, 'Take this child away and nurse it for me. I shall pay you myself for doing so.' So the woman took the child away and nursed it. When the child grew up, she brought him to Pharaoh's daughter who treated him like a son; she named him Moses 'because', she said, 'I drew him out of the water.' (Exodus 2:1-10)

© Brukenthal National Museum

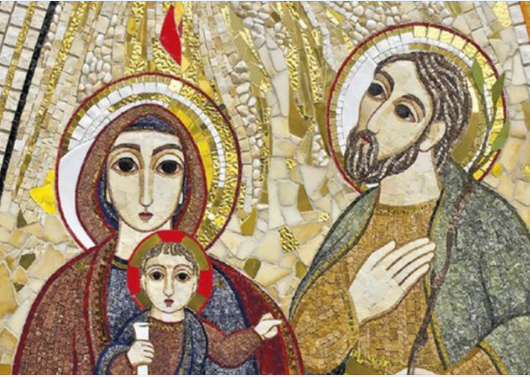

Jacob Jordaens (Antwerp, Belgium 1593 – 1678), The Holy Family, around 1625-30, oil on canvas, 113.1 cm x 118.5 cm, Sibiu, Romania, Brukenthal National Museum.

Month of December.

With this reflection, we conclude this journey we undertook by the figure of Saint Joseph, who was the guardian of the Holy Family. We do so with the help of a painting which is in some ways exceptional. It was done by one of Antwerp's most important painters, second in fame only to the great Peter Paul Rubens, whose main collaborator he became after Anthony Van Dick's departure for Italy.

© KHM-Museumsverband - https://www.khm.at/en/objectdb/detail/318/?offset=2&lv=list

Agnolo di Cosimo, known as Bronzino (Monticelli, Italy 1503 – Florence, Italy 1572), Holy Family with St. Anne and the Infant St. John, around 1540, oil on poplar wood, 126.8 cm x 101.5 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Month of November.

Today we contemplate on this mature painting by Bronzino, who became one of the favourite painters of the Medici, the family that ruled Florence. The fact that the painter was by then famous is also shown by the signature: on the stone under the left foot of Jesus we can read BROZINO FIORENTINO (Bronzino of Florence).

Image © website Museo Nacional del Prado

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Seville, Spain 1617 – 1682), The Holy Family with a Little Bird, around 1650, oil on canvas, 144 cm x 188 cm, Madrid, Spain, Prado Museum.

Month of October.

Contemplating this painting always brings great joy, because the painter favoured the simple, everyday dimension of the life of Jesus' family. They had finally returned to Nazareth, as evidenced by the carpenter's tools on the right side of the scene.

Albrecht Altdorfer, Ruhe auf der Flucht nach Ägypten, 1510, Cat. No. 638B

Albrecht Altdorfer, Ruhe auf der Flucht nach Ägypten, 1510, Cat. No. 638B

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie / Jörg-P. Anders

Link: https://we.tl/t-xo1zjQWcfQ

Albrecht Altdorfer (Regensburg, Germany 1480 – 1538), Rest on the Flight into Egypt, 1510, oil on lime wood panel, 58.2 cm x 39.3 cm, Berlin, Germany, Gemäldegalerie.

Month of September.

This small painting is above all a painter’s act of faith and devotion. This can be seen in the inscription with which he signed the work, in the bottom left corner, on the round base of the fountain's basin: ‘The painter Albert Altdorfer of Regensburg has consecrated this gift for his salvation to you, Holy Mary, with a faithful heart.’ I am moved by his desire to put his talent for painting at the service of his salvation. And he does it in a commendable way with a small but very elaborate work.

Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, Italy 1431 – Mantua, Italy 1506), Holy Family, 1495-1500, egg tempera and linseed oil on canvas, 75 cm x 61.5 cm, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Inv. Gal.-Nr. 51

Month of August.

This work of art by the great Mantuan painter was almost certainly made for private devotion. We know little about the painting's history, but if we stare at it and contemplate it, before this work we can read into the folds of its meaning and listen to the emotions it arouses in us.

© Tours, musée des Beaux-Arts, cliché Dominique Couineau

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, (Leiden, Netherlands 1606 – Amsterdam, Netherlands 1669), The flight into Egypt, 1627, oil on wood, 26 cm x 24 cm, Tours, France, Musée des Beaux-Arts, gift by Mme Benjamin Chaussemiche, 1950. Inv. 1950-13-1

Month of July

This representation of the flight of Jesus’ family into Egypt is truly unique. The first thing that strikes us is the small size of the painting. This suggests that the young painter, still in his early twenties, must have painted it for a client - whether lay or religious - who wanted to keep the work in his home for private devotion.

Bernhard Strigel, (Memmingen, Germany 1460 – 1528), Holy Family, 1505-1506, oil on fir wood, 78 cm x 55 cm, Nuremberg, Germany, Germanisches National Museum

Month of June.

The panel, along with nine others, all of them in Nuremberg, was part of the altarpiece of the chapel dedicated to St. Anne in the parish church of Mindelheim, Germany. The chapel was the burial place of the Rechberg and Frundsberg families, who asked the painter to depict the family of Jesus and his ancestors.

Master of the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece (active in Cologne, Germany from 1470 to 1510 approximately), Holy Family, around 1495-1500, mixed technique on oak wood, 26 cm x 19,9 cm, Frankfurt, Germany, Städel Museum.

Month of May.

We do not know the name of the painter who painted this exquisite scene. He takes his name from a triptych - now in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, Germany - depicting St Bartholomew and 6 other saints, originally placed in the Carthusian monastery in Cologne, as evidenced by the depiction of a Carthusian monk kneeling in the middle, next to St Bartholomew, then moved to the church of St Columba, in Cologne, at the behest of a wealthy city merchant.

Francisco de Zurbarán, (Fuente de Cantos, Spain 1598 – Madrid, Spain 1664), The Flight into Egypt, 1630-35, oil on canvas, 150 cm x 159 cm, Seattle, Art Museum

Month of April.

The episode of the flight into Egypt is reported only in the Gospel of Matthew: “After they [the Magi] had left, suddenly the angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, 'Get up, take the child and his mother with you, and escape into Egypt, and stay there until I tell you, because Herod intends to search for the child and do away with him.' So Joseph got up and, taking the child and his mother with him, left that night for Egypt, where he stayed until Herod was dead” (Mt 2:13-15a).

Domenikos Theotokopulos, known as El Greco (Candia, Greece 1541 – Toledo, Spain 1614), St. Joseph and the Christ Child, 1597-99, oil on canvas, 289 cm x 147 cm, Toledo, Spain, Chapel of Saint Joseph

19 March, Solemnity of Saint Joseph

I am sure some of you are wondering why I have not chosen a picture of the Holy Family for this month. The simple answer is that I wanted to make a special dedication to St Joseph in this month of March. In fact, this painting - which I personally find wonderful - made me think that the whole Family of Jesus is actually present. As a matter of fact, Mary is on this side of the painting, in our same position, smiling and contemplating her little Jesus who has run to embrace his father, to cling to him trustingly, to receive his affectionate caress. If a camera had existed in those days, this painting would be a picture taken by Our Lady!

Martin Schongauer (Colmar, France 1440/5 – Breisach, Germany 1491), The Holy Family, 1480-90, oil on panel of red beech wood, 26.3 cm x 17.2 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

February.

Martin Schongauer is most famous for his work as a copperplate engraver. He produced around 130 engravings, and the fame of his works, while he was still alive, was such that a famous painter and engraver like Albrecht Durer decided to travel from his native Nuremberg to Colmar just to meet the artist who had inspired him so much. Nevertheless, as there was no WhatsApp or TV at the time, it was only when he arrived in Colmar that he learned that Schongauer had been dead for several months.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, Italy 1475 – Rome, Italy 1564), Holy Family, known as “Doni Tondo”, 1506-07, oil and tempera on panel, 120 cm (diameter), Florence, Uffizi Gallery.

Let us begin this year's theme with a great work. It is the Holy Family as depicted by Michelangelo in his only painting on panel that is certainly autograph. We are at the beginning of the 16th century and Florence is home to the three greatest geniuses of the Italian Renaissance: Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo. The panel was painted for Agnolo Doni, a wealthy cloth merchant, a leading member of the Florentine upper middle class who married the noblewoman Maddalena Strozzi on 31 January 1504 (on that occasion Raphael painted the portraits of the couple, also on display in the Uffizi Gallery). The panel was probably commissioned on the occasion of the birth of the daughter Maria, and the choice of theme seems to be a tribute to that important family, gladdened by the arrival of their first-born.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), Canigiani Holy Family, 1505-06, oil on poplar wood, 131 cm x 107 cm, Munich, Germany, Alte Pinakothek

27 December, Feast of the Holy Family.

As for many other works by Raphael, we know the history of this painting too. Painted for Domenico, a prominent member of the noble and rich Canigiani family, perhaps in view of his marriage to Lucrezia Frescobaldi in 1507, the work was noticed by Vasari in the Canigiani heirs' house.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), Madonna of Foligno, 1511-12, oil on wood transferred to canvas, 308 cm x 198 cm, Vatican City, Pinacoteca

This beautiful work of art was commissioned to Raphael by Sigismondo de' Conti, a distinguished humanist from Foligno, Italy and secretary of Pope Julius II. The painting was meant to be a thanksgiving to the Virgin for having saved his house in Foligno, struck by lightning or a fireball. We can see a reference to this story both in the beautiful landscape in the background - we can see a small town and a solid house about to be struck by a flaming trail coming down from the sky - and in the little angel in the centre of the painting holding an empty plaque, probably destined to commemorate the vow fulfilled by the Virgin.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), The Marriage of the Virgin, 1504, oil on wood, 170 cm x 117 cm, Milan, Italy, Pinacoteca di Brera.

October.

The first thing that strikes us in this masterful work by a young Raphael is the building in the background. It is quite elegant, with a central plan, and has a portico all around it and a dome. The two opposite doors are open and therefore allow our eye to follow the landscape and the sky beyond the building. Its shape seems circular, even though it is actually built with 16 sides. We can also see a polygonal staircase all around the building, and a foreshortened squared floor.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), St. Michael, 1505, oil on wood, 30 cm x 26 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum.

29 September, Feast of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael.

The work was mentioned in 1587 in a sonnet by Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, a Milanese painter and man of letters, who blamed a rich but ignorant fellow citizen who sold to Ascanio Sforza, Count of Piacenza, this small painting together with another, of equal size, representing St. George and the dragon. Both paintings went from Piacenza into the collection of Cardinal Mazzarino and finally into the royal collection of Louis XIV, which today constitutes the most important, notable part of the Louvre Museum.

Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520), The transfiguration, 1518-20, rich tempera on panel, 405 x 278 cm, Vatican, Vatican Pinacoteca.

6th of August, feast of the Transfiguration.

We have already written about this magnificent board (cf. month of October 2017) presenting the mysteries of the Rosary. Its beauty is such, its fame is so great, that we wish to add other and different considerations on the same.

First of all, let us remember the great importance of the painting. It was commissioned to Raphael by Cardinal Giulio De' Medici, cousin of Pope Leo X (Giovanni De' Medici, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, while Giulio was the son of Giuliano, Lorenzo's youngest brother murdered in the Pazzi conspiracy).

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), Deliverance of Saint Peter, 1513-14, fresco, 660 cm wide, Vatican, Vatican Museums.

Month of July.

This fresco, like the one seen last month, is also located in one of the four rooms of Pope Julius II's apartments. Today, it is called “Heliodorus' room,” and it was once destined for the Pope's private audiences; all four walls had as many episodes in which God's miraculous protection of the Church and its Popes was manifested.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), Disputation of the Holy Sacrament, 1509, fresco, 500 cm x 770 cm, Vatican, Vatican Museums.

14 June, Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ (Corpus Christi).

The large fresco is part of the decoration of one of the 4 Raphael Rooms, painted with his students for Pope Julius II of the Della Rovere family, who entrusted the young genius from Urbino with the task of painting the rooms of his private apartment.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), Madonna and Child with the Infant John the Baptist (known as Madonna of the Goldfinch), around February 1506, oil on wood, 107 cm x 77 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi.

Month of May.

The peculiarity of Raphael's painting is not so much the subject (the Virgin was often represented with the little Jesus and his cousin John the Baptist) but the choice to set the scene in a completely open space. The panel was painted for Lorenzo Nasi, who wanted it in his Florence’s house on the occasion of his marriage to Sandra Canigiani, held on February 23, 1506.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), The Deposition, 1507, oil on wood, 184 cm x 176 cm, Rome, Galleria Borghese.

10 April, Good Friday.

This beautiful painting is signed and dated (RAPHAEL URBINAS MDVII) on the rock in the bottom left corner, showing that it was an important work for the painter as well.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), The Annunciation, 1502-1504, tempera on panel, 27 cm x 50 cm, Vatican City, Vatican Museums.

25 March, Solemnity of the Annunciation of the Lord.

This small painting is part of the predella of a large altarpiece depicting the Coronation of Mary. It is called Oddi Altarpiece because it was painted by Raphael for the altar of the Oddi family chapel in the church of San Francesco al Prato in Perugia, Italy. The painting, delivered at the beginning of the sixteenth century, is the youthful work considered the closest to the style of Perugino, the master of the great painter from Urbino.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), Madonna of the chair, 1513-14, oil on panel, 71 cm x 71 cm, Florence, Italy, Palatine Gallery

The size of the panel makes us think of a painting intended for private devotion. The type of chair on which the Virgin was painted (it is a "chamber chair", which was widespread in the papal court during the Renaissance) and the fact that the painting appeared in the Medici Palace in Florence a few decades after its execution lead us to suppose that it was commissioned to Raphael by Pope Leo X, of the Medici family (he was the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent), to make a gift perhaps to his nephew Lorenzo, lord of Florence since 1516.

Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (Urbino, Italy 1483 – Rome, Italy 1520), Sistine Madonna, 1513-14, oil on canvas, 265 cm x 196 cm, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister.

1 January, Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God.

On 6 April 2020 will be the 500th anniversary of the death of Raphael, certainly one of the absolute geniuses of the Italian Renaissance. A selection of his works will accompany us during this year, sure that the pinnacles of beauty reached by the painter from Urbino will help our reflections.

School of Francisco de Zurbarán (Fuente de Cantos, Spain 1598 – Madrid, Spain 1664), Saint Eulalia, 1640-50, 173 cm x 103 cm, oil on canvas, Seville, Spain, Museum of Fine Arts.

10 December, Memory of Saint Eulalia.

Let's start by reading some of the verses that a modern poet, Federico García Lorca, dedicated to the most famous saint in Spain, the martyr Eulalia. They are taken from one of the 18 "Romances" that constitute his most important poetic collection, Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads), published in 1928.

Stefano Maderno (Capolago, Switzerland, 1576 – Rome, Italy, 1636), Saint Cecilia, 1600, marble, Rome, Church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

22 November, Memory of Saint Cecilia.

The story of the beautiful statue in white marble, placed under the altar and the ciborium of the church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, is closely linked to the story of the Roman martyr saint.

Hans Memling (Seligenstadt, around 1436 – Bruges 1494), Saint Ursula protecting her virgin companions, 1489, oil on wood, 45.5 cm x 18 cm, Bruges, Memlingmuseum.

Hans Memling (Seligenstadt, around 1436 – Bruges 1494), Saint Ursula protecting her virgin companions, 1489, oil on wood, 45.5 cm x 18 cm, Bruges, Memlingmuseum.

21 October, Memory of Saint Ursula and companions.

The history of St. Ursula is widely spread in Christian Europe and several legendary elements have been added to it. Her story is said to have taken place between the 4th and 5th centuries AD. She was probably the victim of the persecution of Diocletian or perhaps that of Attila, King of the Huns, who was quite harsh on Christians. Let us try to highlight some essential details of her life.

Gjergj Kola (Durrës, 1967), Saint Teresa of Calcutta, oil on canvas.

5 September, Memory of Saint Teresa of Calcutta.

It feels nice to present a painting of the great saint painted by a young compatriot of hers. When Agnes Gonxhe Bojaxhiu - this is the family name of the one we all know as Teresa of Calcutta - died in the great Indian city, Gjergj Kola was just 30 years old and had moved 6 years before, for political reasons, to nearby Greece.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Seville 1618 –1683), Saint Rose of Lima, around 1670, 145 cm x 95 cm, oil on canvas, Madrid, Lázaro Galdiano Museum

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Seville 1618 –1683), Saint Rose of Lima, around 1670, 145 cm x 95 cm, oil on canvas, Madrid, Lázaro Galdiano Museum

23 August, Memory of Saint Rose of Lima.

The Saint, with her Dominican habit, is on her knees, contemplating the Christ Child, who is sitting on a pillow on the linen basket and is raising his left hand towards the Saint in a caressing gesture, while with his right hand he seems to give her (or is he rather taking them?) roses. From the mouth of the child comes out a Latin inscription that means: "Rose, you will be the bride of my heart." On the floor, next to the basket, there is a book and there are other roses. In the background, on the right, there is a building, which is undoubtedly the convent, partly covered by a bush of roses.

Donatello (Florence 1386 –1466), Penitent Magdalene, 1453-55, height 188 cm, poplar wood with traces of polychrome, Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo

22nd of July: Feast of Saint Mary Magdalene.

Mary Magdalene appears at the beginning of chapter 8 of Luke's Gospel: “Now it happened that after this he made his way through towns and villages preaching and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God. With him went the Twelve, as well as certain women who had been cured of evil spirits and ailments: Mary surnamed the Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, Joanna the wife of Herod's steward Chuza, Susanna, and many others who provided for them out of their own resources.” And then, especially, as it is said in chapters 19 and 20 of the Gospel of John, she was at the foot of the cross, she was in the garden where they laid down the body of Jesus, and she was the first to see the risen one and ran to announce it to the apostles.

Giovanni Odazzi (Rome 1663 –1731), Blessed Theresa and Sancha, 1725, oil on canvas, Rome, Church of Sant’Antonio dei Portoghesi

In Rome, a few steps from Piazza Navona and very close to the more famous Church of St. Augustine, there is a small church of the Portuguese nation, dedicated of course to St. Anthony. In it there are several paintings representing Portuguese saints and blessed, including the one we propose here, which depicts two sisters, both nuns, both blessed. Let us dwell on Theresa.

Giovan Battista Galizzi (Bergamo 1882 - 1963), Entrance of Saint Rita to the monastery, oil on canvas, 1947, Cascia, Italy, Chapel of the urn in the Sanctuary of Saint Rita

Saint Rita of Cascia is one of the most invoked and venerated saints. She was born in 1381 in Roccaporena, a hamlet of Cascia, in central Italy. She was given the name of Margherita, but soon everyone started calling her Rita.

A mild-tempered, humble, obedient and well-mannered girl (her parents taught her to read and to write), from a very young age she became passionate about the Augustinian family, so much to want to take her vows and to attend regularly the monastery of Saint Mary Magdalene of Cascia and the church of St. John the Baptist. But when she was 14, her parents promised her married to Paolo di Ferdinando Mancini, a violent man, and after three years she got married with him. Two children were born from the wedding, perhaps twins: Giangiacomo Antonio and Paolo Maria.

Guidoccio Cozzarelli (Siena 1450 – 1517), Saint Catherine of Siena exchanges her heart with Christ, around 1500, Siena, Pinacoteca nazionale

Catherine was born in Siena on 25 March 1347. Her confessor, Raimondo da Capua - who also became Minister General of the Dominicans - left written testimony of the precocious vocation of this great saint. In 1363, when she was just 16, she became a Dominican tertiary. Illiterate, she learned to read and also to write so as to be able to draw directly on the Holy Scriptures. She obtained special gifts and graces from Jesus, which made her one of the most important mystics in the history of the Church.

Matilda of Ringelheim, marble, Milan Cathedral

Matilda was a woman, a wife, a mother, and a queen who distinguished herself for her extraordinary concern for the poor and the sick, as well as for her intense life of prayer.

February 9: Memory of Saint Apollonia. Guido Reni (Calvezzano 1575 – Bologna 1642), The Martyrdom of Saint Apollonia, 1600-03, oil on copperplate, 28 cm x 20 cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado

The life of the virgin Apollonia, who lived in the third century in Alexandria, Egypt, is practically unknown to us, but Eusebius, in his Church History, reported a passage from the letter of the bishop Saint Dionysius of Alexandria, addressed to Fabio of Antioch, in which he recounted some episodes he had witnessed during the persecution that broke out in the last years of the empire of Philip (244-249): a popular uprising, incited by an evil soothsayer, caused the massacre of many Christians, whose homes were devastated and plundered. The pagans took Apollonia, an unmarried woman, already advanced in age, to whom they struck the jaws making her teeth come out, and threatened to burn her at the stake if she had not spoken impious words with them. "She," Dionysius wrote in his letter, "asked that she be freed for a moment: after this she quickly jumped into the fire and was consumed by it." This event is said to be happened in 249.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (Lyon 1824 – Paris 1898), Saint Genevieve provisioning Paris, 1893-98, oil on canvas, Paris, Panthéon

The life of the Parisian virgin Genevieve is narrated in "Vita Genovefae," written about twenty years after her death. She was born in Nanterre, near Paris, around 422. At the age of 15, Genevieve consecrated herself to God, becoming part of a group of virgins devoted to God who, while wearing a habit that distinguishes them from other women, did not live in the convent, but in their homes, dedicating themselves to works of charity and penance.

Master of the Lyversberg Passion (working in Cologne between 1460 and 1490), Coronation of Mary, around 1464, 101,6 cm x 133 cm, oil on oak wood covered with canvas, Munich, Alte Pinakothek

The representation of Mary's coronation as Queen of Heaven and Earth is truly solemn. The first thing we notice is that the earth - our world - has practically disappeared from this painting. There is a little mention of it in the two edges of the lawn at the bottom right and left corners, where Johann and Margarete Rinck, the couple who offered the painting for the church of Santa Colomba in Cologne, are kneeling. Today, in the museum of Munich, in addition to this panel, which was certainly the central and main part, there are two other small panels representing St. James the Greater and St. Anthony the Hermit, which were part of the same polyptych. There were certainly other parts in it, but they have been lost.

Annibale Carracci (Bologna, 1560 – Rome, 1609), Assumption of the Virgin, around 1600-01, 245 cm x 155 cm, oil on wood, Rome, Church of Santa Maria del Popolo

This panel is located in the first chapel on the left of the high altar of the famous Roman church in Piazza del Popolo. The chapel was purchased in July 1600 by Tiberio Cerasi, who was the Treasurer General of the Apostolic Camera. Cerasi, who wanted to be buried there, had the chapel rearranged and enlarged by the famous architect Carlo Maderno and commissioned the two most famous painters of the time to embellish the three walls: Annibale Carracci was commissioned to paint the large panel of the main wall, whereas Caravaggio was asked to paint two canvases for the side walls with The conversion of St. Paul and The Martyrdom of St. Peter. Today, it is still possible to admire all three paintings and the tomb of Cerasi, who died on 3 May 1601, when only the panel of the Assumption was already in place probably. In fact, we know that the chapel was consecrated on 11 November 1606.

Domenico Theotocopoulos, known as El Greco (Candia, 1540 – Toledo, 1614), Pentecost, 1605-10, 275 x 127 cm, oil on canvas, Madrid, Museo del Prado

The large canvas by El Greco, which develops vertically like its figures, presents two focal points on which the scene is built. In the top, in the place where the Apostles are gathered with Mary and the women, the darkness is torn and the dove, symbol of the Spirit that breaks in and emanates its strength, appears in the form of flames on the characters that crowd the lower part of the painting. Let us count them: Mary is at the centre, five are on her right and four on her left; another three are on the sides of the intermediate ground, and finally two - the closest to us onlookers – are in the foreground with their backs to us. There are fifteen of them, as the book of Acts tells us (cf. 1:14).

Master Bertram (Minden, circa 1345 - Hamburg, 1415), The Ascension, circa 1390, oil on wood, cm 52 x 51, Hannover, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum

The small wood piece by the German painter is part of a large painting - the Polyptych of the Passion - where we find several episodes describing the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus.

Matthias Grűnewald (Wűrzburg, around 1475 – Halle, 1528), The Resurrection, 1512/16, oil on panel, 269 cm x 143 cm, Colmar, Unterlinden Museum

This large panel is part of a monumental polyptych, commissioned in 1512 to Matthias Grünewald by the Sicilian prior Guido Guersi, for the altar of the church of the Monastery of Sant'Antonio Abate under the mountain, known as the Grand Ballon d'Alsace, just outside the village of Issenheim.

Fra Angelico (Vicchio, Italy, around 1395 – Rome, 1455), Noli me tangere, around 1440-41, 180 cm x 146 cm, fresco, Florence, Museo di San Marco

It's a garden indeed, the place where they had buried him! There are flowers and plants, slanting their branches to the sky. The place is divided by a fence that marks the boundary and, on the left, the new tomb, open. At the centre are the two characters who are the protagonists of the scene. Let us observe them. Better, let us contemplate them.

Antonello from Messina (Messina 1430 -1479), The Crucifixion, 1475, oil on wood, cm 59,7x42,5, Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts.

The small painting was certainly to be used for the private devotion of an important person who had commissioned the painting. Antonello put his signature on the lower left cartridge where he wrote: "1475 - Antonellus messaneus me pinxit" (Antonello of Messina painted me in 1475).

Simone Martini (Siena 1284 - Avignon 1344), The Ascent to Calvary, around 1335, tempera on wood, 30x20 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum

The ascent to Calvary was the verse of one of the compartments of a small polyptych for private devotion, painted on both sides. When it was open, four scenes from the Passion of Christ could be seen in succession, the ascent to Calvary (at the Louvre in Paris), the Crucifixion and the Descent from the Cross (at the Royal Museum in Antwerp) and the Deposition in the tomb (at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin). It was therefore a meditation on the mystery of the last moments of Jesus' life.

Tiziano Vecellio, also known as Titian (Pieve di Cadore, c. 1490 – Venice 1576), The Crowning with Thorns, c. 1570, oil on canvas, 280 cm x 182 cm, Munich, Alte Pinakothek

What is impressing about Titian’s great painting is the excitement of the scene. After all, the Gospel story is already dramatic, as we can see from Mark’s passage: "And the soldiers led him away into the hall, called Praetorium; and they call together the whole band. And they clothed him with purple, and platted a crown of thorns, and put it about his head. And began to salute him, Hail, King of the Jews! And they smote him on the head with a reed, and did spit upon him, and bowing their knees worshipped him" (Mk 15:16-19, but also cf. Mt 27:27-30 and Jn 19:2-3). Jesus is abandoned in the centre of the scene, completely at the mercy of the four soldiers who surround him. The movement of the scene seems to be directed by the skilfully handled reeds. We can only imagine the pain that Jesus felt after each reed blow, because with the blow came the sticking of a thorn in his head.

Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio (Milan 1571 – Porto Ercole 1610), The flagellation, 1607-1608, oil on canvas, 286 cm x 213 cm, Naples, Museo nazionale di Capodimonte

After the dramatic killing of Ranuccio Tomassoni on 28 May 1606, Caravaggio was forced to flee Rome. Chased by the guards of the Papal State, at the end of that year he stopped in the nearby city of Naples, where he found protection and enough calm to resume painting.

Duccio di Buoninsegna (Siena, c. 1255 – 1318 or 1319), The arrest of Jesus, 1308-1311, tempera on wood, 50 cm x 76 cm, Siena, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo

What we present is one of the twenty-six scenes of the Passion of Jesus that are represented in fourteen panels and adorn the back of the larger panel, whose main façade is dedicated to the Madonna on the throne with Child venerated by angels and saints.

Hieronymus Bosch (‘s-Hertogenbosch, 1453 –1516), Adoration of the Magi, c. 1495, oil on panel, 138 cm x 144 cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado

The scene represented by the great Dutch painter shows some traditional elements and some innovative and very particular elements, starting with the choice of the triptych shape. In the side panels, he painted the two sponsors of the work with their respective patron saints: Peter Bronckhorst with St. Peter and his wife Agnes Bosshuysse with St. Agnes. The beautiful landscape on the background of the three panels, in addition to showing the beauty of nature and the abundance of water, shows, to a careful observer, details that allow us to glimpse their symbolic interpretation: in the central panel, in the background there are two armies facing each other, whereas in the right side we see two passers-by who are assaulted by two wolves.

Francisco de Zurbaran (Fuentes de Cantos, 1598 - Madrid, 1664), Immaculate Conception, about 1635 - oil on canvas, - Sequence, Diocesan Museum.

The great Spanish painter, who carried out his activity mainly in Seville, interprets the subject of the Immaculate Conception according to classical canons: Mary, very young represented, is praying, with her hands joined, wearing a long white tunic and the cloak, of an intense blue, which is spread out to form a perfectly balanced pyramidal volume. Beautiful and precious is the jewel placed on the neckline of the dress, which reproduces the monogram (an A intersected to an M) of the angelic greeting: “Ave, Maria” ("Hail, Mary").

Pietro Lorenzetti (Siena, c. 1280/85 – c. 1348), Last Supper, 1310-20, fresco, Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi

The scene, built around a table, takes place inside a magnificent hexagonal loggia (which is very much reminiscent of the structure of the pulpit of the Cathedral of Siena by Nicola Pisano). There, we can see the elements of tradition: the table is fitted out and the bread and the glass of wine are placed on it; the twelve are around Jesus – who is at the centre of the composition, dominating it – placed in a perfect arch, six on the left half and the other six on the right half; John has placed his head on the chest of the Master, whereas Judas is the only one without an aureole, thus testifying that the devil has already put in his heart the idea of treason (cf. Jn 13:2). Among the apostles there seems to be a slight movement, perhaps because they are caught at the moment when they are wondering who and how it will be possible for one of them to betray Jesus.

Raphael, Raffaello Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520), The Transfiguration, 1518-20, oily tempera on wood, cm 405 x 278, Vatican City, Vatican Museums

This impressive work - perhaps the last of the great painter from Marche region – presents, for the first time together, two distinct episodes of the Gospel of Matthew, which are narrated in succession in the first part of chapter 17. They are the transfiguration (17:1-8) and the healing of the possessed child (17:14-18).

El Greco, Dominikos Theotokopoulos (Candia, 1541 – Toledo, 1614), Healing of the blind man, around 1570, oil on poplar wood, cm 65.5 x 84, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie

“Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom, and healing every disease and sickness among the people” (Matthew 4:23).

Gerard David (Ouwater, 1450-60 – Bruges, 1523), The wedding at Cana 1523, oleum on wood, cm 100 x 128, Paris, Musée du Louvre

The work of the Flemish painter is very rich from the iconographic point of view. Full of figures, beyond the accurate reproduction of the Gospel (cf. John 2, 1-11), the scene shows different levels.

Piero della Francesca (Borgo San Sepolcro, c. 1420 – 1492), The Baptism of Christ, c. 1445, tempera on panel, 167 cm x 116 cm, National Gallery, London

The representation of this evangelical scene is very peculiar: it doesn’t intend to tell the event in its actual reality, but rather through its multiple meanings.

Doménikos Theotokópoulos, known as El Greco, (Heraklion, around 1541 – Toledo, 1614), The Holy trinity, 1577-79, oil on canvas, 300 x 170 cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado

The great painting by the Spanish painter is almost entirely occupied by the figures represented. There is no landscape, only the golden light on top, where the dove of the Holy Spirit is hovering around, and the low clouds on which the characters stand. In fact, the scene is entirely divine, it represents the Trinity.

Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg 1471 –1528), Christ among the Doctors, 1506, oil on poplar panel, 65 cm x 80 cm, Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

This intense and peculiar representation of the well-known evangelical episode was made by Dürer in just 5 days during his second stay in Venice (in addition to the artist’s monogram, we can read Opus Quinque Dierum, meaning “made in five days”, on the slip of paper sticking out of the tome in the lower left corner).

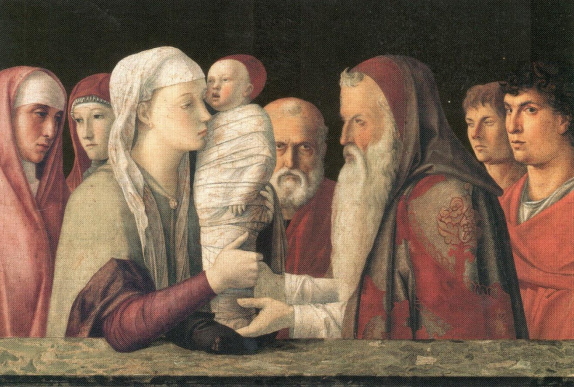

Giovanni Bellini (Venice, c. 1433 – 1513), Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, c. 1460, tempera on panel, 82 cm x 106 cm, Venice, Fondazione Querini Stampalia

The panel presents a crowd of people in a small space behind a marble balustrade. The picture is probably rich in meaning for the artist if, as it seems, the young man portrayed on the right is Giovanni Bellini himself, while the woman on the opposite side should be his wife Ginevra.

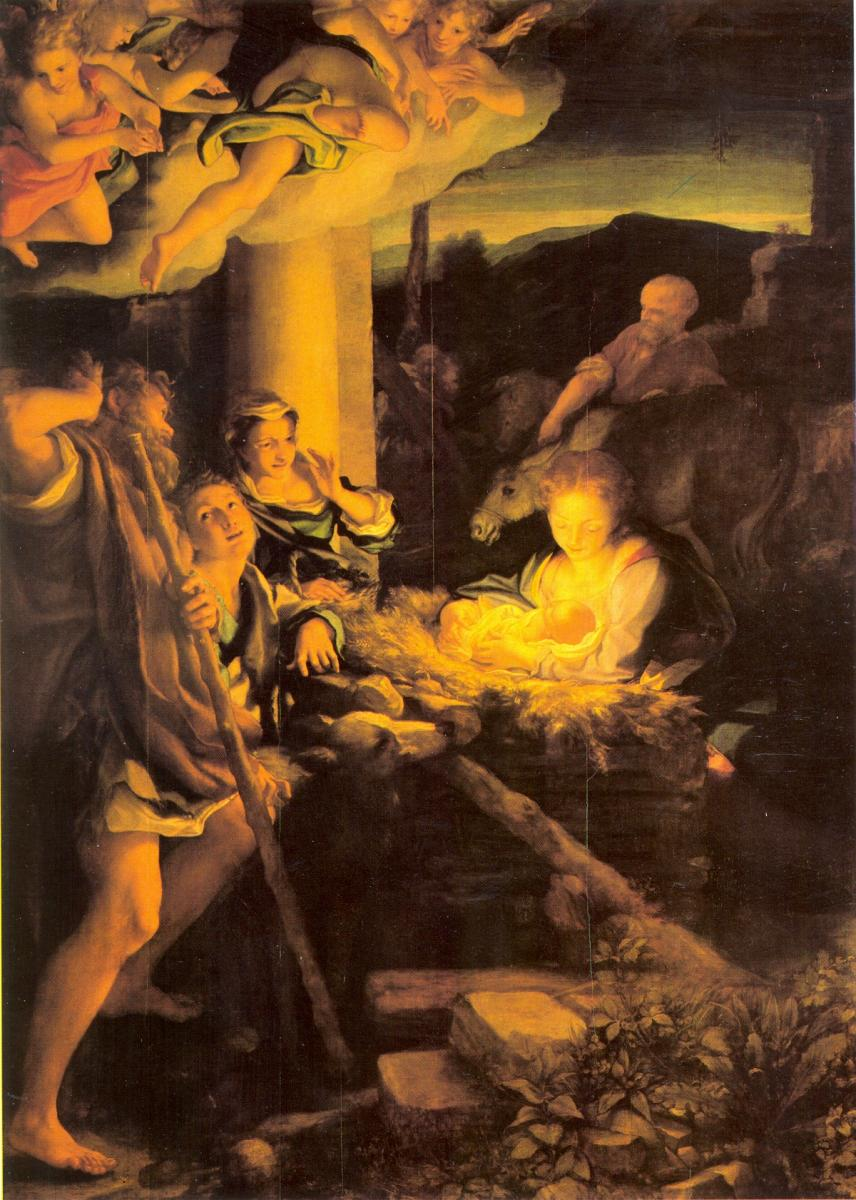

Antonio Allegri, known as Correggio (Correggio, Italy 1489 – 1534), Nativity, 1522-1530, oil on poplar wood, cm 256.5 x 188, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie

This large table that Correggio painted for the chapel of the Pratoneri family in the church of San Prospero in Reggio Emilia, Italy, represents an unusual scene. It is night, the special night in which Mary gave birth to Jesus. We know that something special happened that night for there is a warm, very intense light emanating from the child. It is a light that illuminates directly Mary, and then hits the other protagonists of the painting: the woman, the shepherds, the angels and even Joseph, who’s on the background.

Jacopo Carucci, known as Pontormo (Pontorme, 1494 – Florence, 1557), Visitation, around 1528-30, oil on board, cm 202 x 156, Carmignano, Italy, Prepositure of Saints Michael and Francis

Pontormo has set the meeting between Mary and Elizabeth in a dark city street, where some bare, off-scale buildings are visible. The darkness of the scene is pierced by the light that is reflected on the figures in the foreground, on the faces and especially on the drapery.

Lorenzo Lotto (Venice, c. 1480 – Loreto, 1556), Recanati Annunciation, 1527, oil on canvas, 166 cm x 114 cm, Recanati, Civic Museum

The environment in which the scene described by Luke (1: 26-38) takes place is a small room, with a few everyday objects used by Mary, the young woman living in it. On the right side of the painting there’s the mighty and real (we can actually see his shadow on the floor) figure of the angel Gabriel, who almost seems to have glided through the beautiful arched entrance. Above, in the clouds, the figure of God, the one who chose Mary to make her become the Mother of the Lord, His Son Jesus, and the one who sent the angel.